Narratives Strategies for Racial Justice: The Visuality of Truth Telling

This past weekend, I, along with 60 NYU graduate students, took a trip to visit The Legacy Sites in Montgomery, Alabama. During our time there, we visited the Equal Justice Initiative offices, The Legacy Museum, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and previewed the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. This trip was part of a course I'm currently taking titled Narrative Strategies for Racial Justice and Equality, led by Bryan Stevenson (EJI). This blog post draws from my reflection notes during my visit to The Memorial for Peace and Justice and is part of a larger academic paper I submitted for this course. My final paper explores the various visual methods used at The Legacy Sites to articulate decolonial aesthetic representations and narratives, which are essential to achieving justice and healing.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a space for acknowledging and reflecting on the legacy of racial terror in America. This memorial is the first in America to remember the legacy of Black Americans who were terrorized by violent and public racial lynchings. Read more about the Memorial and the importance of confronting the truth about our history here.

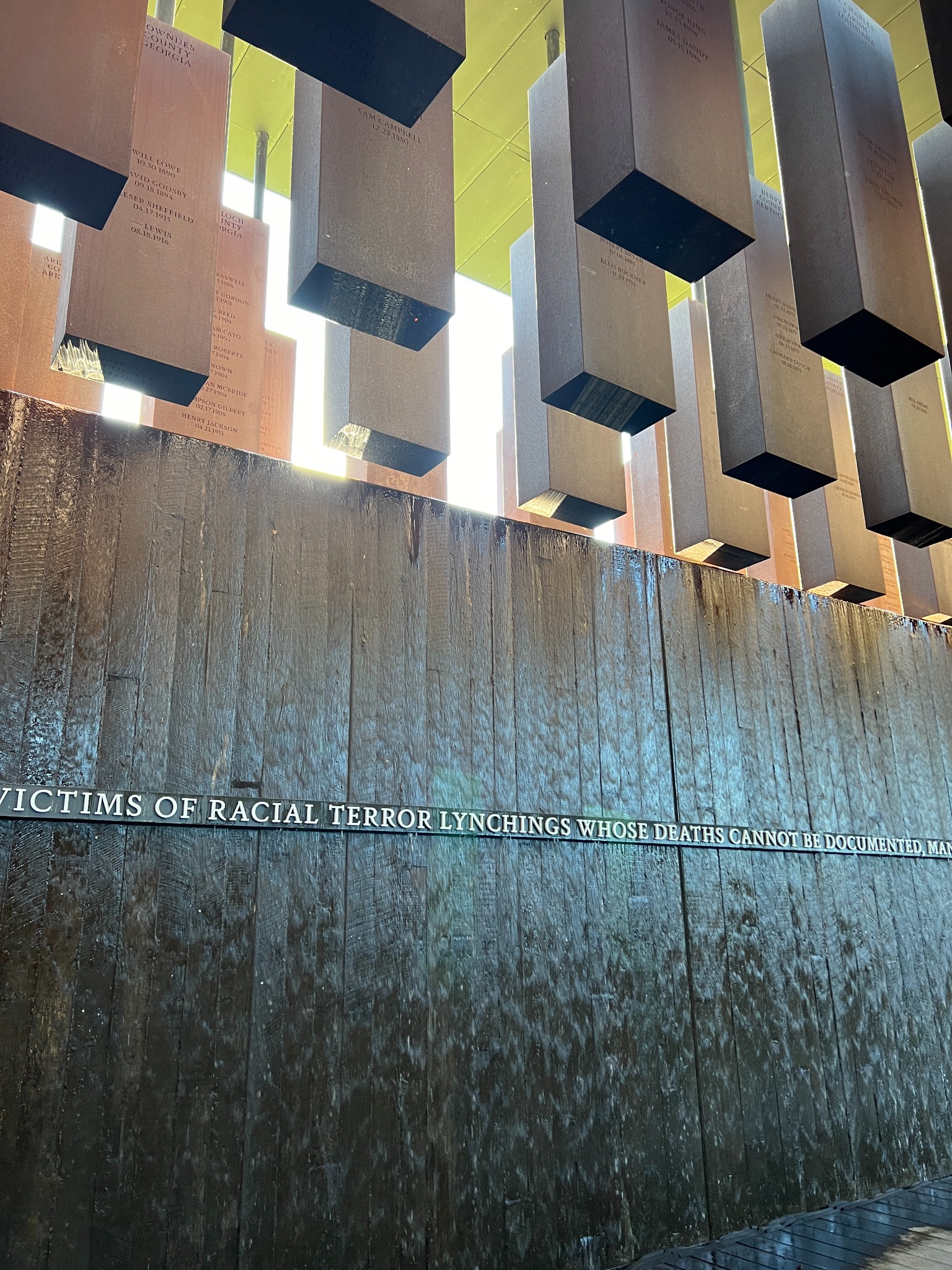

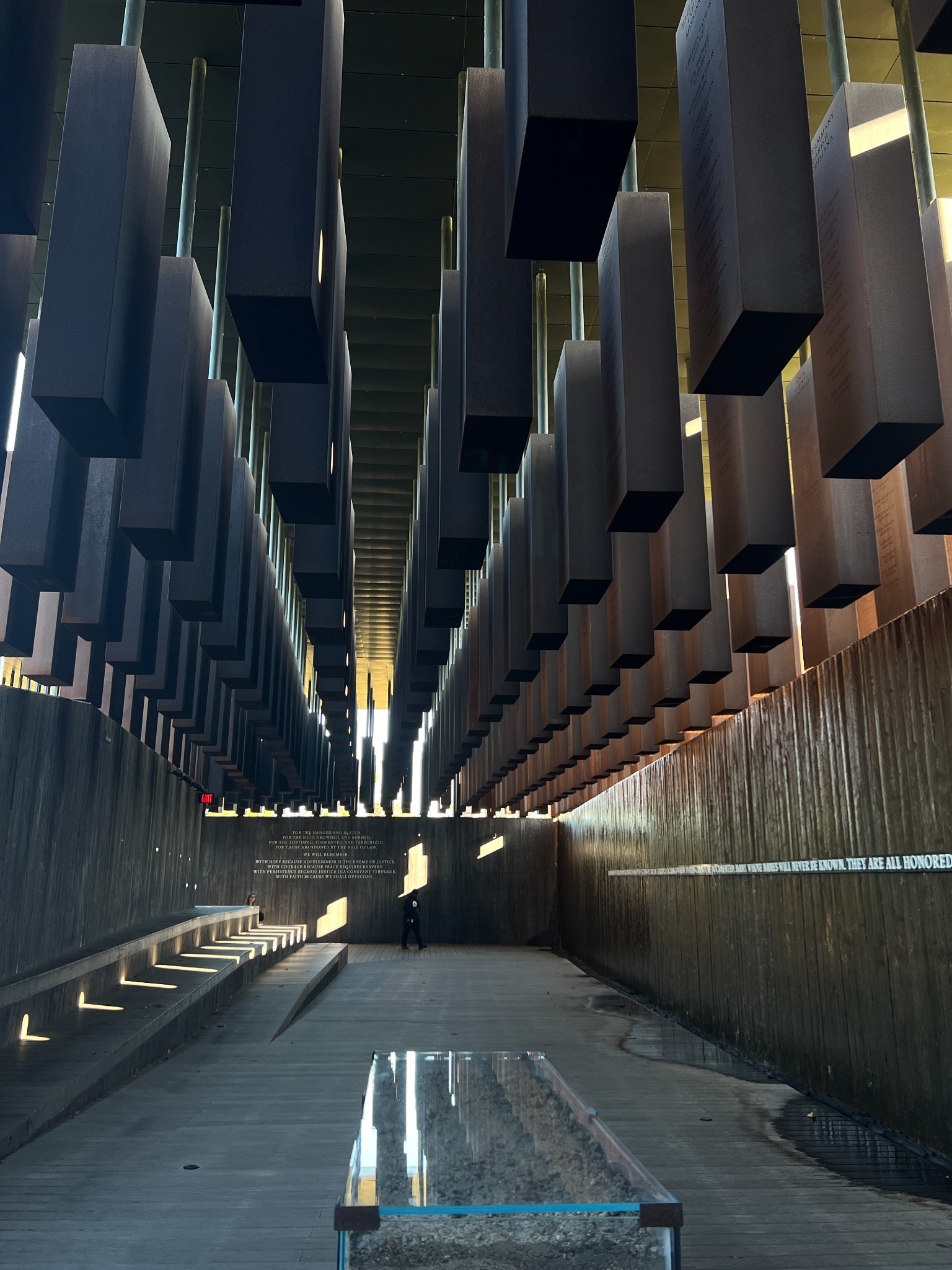

When I first entered the Memorial for Peace and Justice, I saw 800 large copper-colored steel structures. These monuments hung from the ceiling, but were resting on the floor when I first entered the memorial. As I began walking through the monuments, they gradually lifted to eye level. The monuments started to get suspended higher and higher until eventually, I was walking right below them. They hung high enough for me to read the inscriptions underneath. The pathway sloped to evoke this change, but it wasn't obvious. The deliberate positioning and movement of the monuments felt symbolic.

My experience observing the names, dates, counties of the individuals being honored, being within them and walking through them, is profound. There’s a point in which I can almost touch one of the monuments. I’m forced to look up at the monuments in a way that screams “look at this history, look at what happened”.

Near the end of the path through the steel structures, there is a water fountain wall. I asked one of the staff members why water flowed down this wall, and he explained that the waterfall represents the tears and pain of the victims. It honors not only their loss but also holds space for the emotions they were made to endure.

When you walk down to the next section, the same monuments lie flat like tombstones. With the hanging monuments, we acknowledge the sheer amount of loss, the intensity of the loss, and a truth that has always been concealed. With the horizontally laid monuments, we mourn. We identify with the loss; we humanize the pain. Seeing the same names again brings up this feeling of disbelief – how did the same horror keep happening, yet no one was ever held accountable?

The confrontation imposed by these monuments, whether hanging or lying, activates a truth about history we were told to forget. I recall the words I heard in the museum, also echoed by our shuttle bus driver on the way to the memorial – 'these are all cold cases.' The trauma of these spectacle lynchings likely haunted every Black person living in the South during that time.

The breeze is fresh. It's quiet. The birds are chirping in a beautiful tune that isn't heard often. There is peace. It feels like peace and truth. There isn't as much information in this memorial as there is in the museum. It's just the truth. Arriving at the Memorial after spending hours at The Legacy Museum, I am, as Professor Nicholas Mirzoeff would say, fully de-anesthetized. I pause to reflect by the flat monuments. My name is Manahil Munim, it’s not a common name, especially not in North America. I don’t encounter my name often. Even so, I try to imagine walking through this memorial and seeing my last name, or my first name, or a family name. I sit with that thought. It prevents me from moving forward.

There are names on these monuments that have connections to the people that walk through them, and I feel this is exactly what “activates the visible”. The feeling that we are still existing in this history and involved in this narrative reminds me how important narrative work is. I think about the people that were in the lynching crowds celebrating these murders. They exist in a present not tainted by this violence.

There’s a third area of monuments I’m approaching, and I read a sign that says, “Community Reckoning”, “honoring communities that have engaged in local remembrance and reckoning with the history of lynching and racial terror”. I sit down to read the memorial text of the lynchings. From all that I’ve read so far, the underlying narrative was that the appropriate and expected response to disruptions of the racial power hierarchy was to kill the Black person and instill enough fear that their family would flee.

The worst part is reading about the lynchings with no identifiable name of the victims. I recall my time at The Legacy Museum, where I read news clippings from the post-emancipation era. People published ads to locate family members they were separated from during slavery. The pain of separation and isolation of slavery also reveals itself here. These victims were so dehumanized that they were not even remembered by names and were separated from those that would remember. Black people weren’t seen as human so white people became desensitized to their own violence (Stevenson). But still, I can’t fathom how they could have done all of this, with their own bare hands, while manufacturing consent for it.

Post a comment